Orfeo ed Euridice (original 1762 version)

Opera in three acts

Libretto by Ranieri Calzabigi

First performance: Vienna, October 5, 1762

Cast:

Orfeo (alto castrato/countertenor)

Euridice (soprano)

Amore (soprano)

Chorus

Program Notes by Martin Pearlman

When I first began to listen to Gluck's Orpheus opera years ago, I could not reconcile what I read about the opera with what I heard. The history books all tell us that this is a revolutionary work, a milestone in the history of opera. In it, Gluck and his librettist Calzabigi introduced sweeping reforms in an effort to make opera seria more natural and dramatic, and their success has been acclaimed for over two hundred years. Yet, despite the beauty and simplicity of the music and despite its famous underworld scene with demons and furies, the opera as a whole seemed curiously undramatic. It was only years later that I learned the reason: what we generally hear in performances of the opera is not the bold, innovative work that Gluck originally wrote. Rather, it is most often either a later version by Gluck himself, an adaptation by Berlioz, Liszt or others, or a composite of more than one version, all of which have watered down the succinctness and impact of the original drama.

Orfeo ed Euridice was first presented in Vienna in 1762. That initial version was in Italian and featured in the title role the famous alto castrato Guadagni, the same singer for whom Handel had written arias in Messiah and Samson. Some seven years later, in 1769, Gluck transposed much of the music higher for performances by the soprano castrato, Giuseppe Millico, but dramatically the work was essentially the same. Gluck and his librettist Calzabigi explain some of their reforms in a manifesto: they have done away with the traditional da capo arias, because the drama is weakened by repeating long sections of music that have been sung once already; and the drama should not wait while singers show off their virtuosity in cadenzas. What was paramount for them was expressing the words directly and simply, in order to project the drama. Many musical numbers in Orfeo are run together to create a greater dramatic flow than was possible in operas earlier in the century, and, with the orchestra playing throughout the opera, there are no secco recitatives to break the dramatic continuity. For Gluck, Italian opera needed to be purged of the "abuses" introduced by vain singers and compliant composers. "I believed that my greatest labor should be devoted to seeking a beautiful simplicity . . . and there is no rule which I have not thought it right to set aside willingly for the sake of an intended effect."

In 1774, Gluck mounted a new production in Paris and thoroughly reworked the opera to suit French tastes. The revolutionary Orfeo was now transformed to a conservative Orphée. Not only was it translated into French, which necessitated rewriting most of the recitatives, but the role of Orpheus was rewritten for a high tenor voice. This latter change, dictated by the French distaste for castrati, meant that the demigod singer Orpheus would no longer have the ethereal quality of the high castrato but a more heroic tenor sound. The colorful, innovative orchestration of the original had to be simplified for the larger orchestra and larger hall of Paris. But most importantly for the drama, Gluck acceded to French tastes by adding a good deal of new ballet music, as well as a few new arias (the latter including some bravura writing of the kind he had renounced for the original version). The short opera was now considerably longer and the conciseness of the drama was badly compromised. Despite its success with the French public, the new version was criticised by some as being too long to sustain interest in such a simple story.

The French Orphée et Euridice does have many wonderful features, not the least of which is some of Gluck's most famous ballet music, including dances for the blessed spirits and for the furies. For that reason, as well as the difficulty of finding a male alto who can sustain the work, modern performances have often presented either the later French version or a composite of music from the two versions--or even one of the later adaptations by other composers.

To present the original Italian version, we must sacrifice a few well-known numbers which Gluck added later, but in doing so, we recover the forward movement of the drama which so impressed the first audiences. The work is still a pastoral drama with a simple story, and, for that very reason, it is sensitive to being weighed down by the padding which Gluck added for his Parisian audiences.

The lieto fine

Why, in a work that attempts a revolution in drama, do we have the unexpected happy ending? The Greek myth ends tragically for Orpheus. It is a story not only of the power of his music but of the failings of his humanity. But here, at the end of the opera, Eurydice is suddenly restored to life by Love. Generally, the new ending has been attributed to the fact that the premiere was presented for the emperor's nameday: since the story could be taken allegorically, it should not leave the royal consort in hell. There is no doubt a strong case for this, but it is also more than a matter of politics. A happy ending affected by the power of Love may be foreign to the Greek myth, as it would be to our modern theater, but it fits Enlightenment theater, where we are presented with an idealized world.

The true aim of Gluck's reform was to depict the emotions of the characters in a direct and heartfelt way, and that reaches its height before the happy ending. We feel Orfeo's passion, and his aria Che faro senz' Euridice (What will I do without Euridice) after he loses his lover, is justly famous for its unexpected poignancy in a major key. Gluck's opera points the way to opera of the next century. His dramas were esteemed by Berlioz and admired by Wagner, and his name is engraved next to Beethoven's and Mozart's on many nineteenth-century concert halls. Rousseau spoke for many when he described Gluck's operas as the beginning of a new era. Audiences of the time found them unprecedented in their dramatic impact

Instruments

Gluck's orchestration is unusually colorful and innovative, particularly in the original Italian Orfeo, and musical examples from it appear in Berlioz' important book on orchestration. The famous aria, Che puro ciel, which Orpheus sings when he first beholds the transcendent light of the underworld, has an extraordinary orchestral texture: small sparkling figuration in the solo flute and solo cello play against a sustained melody in the oboe, all of it set against a halo of orchestral sound. (Gluck had to simplify this detailed orchestration for the large hall in Paris.) In other numbers, he calls for several unusual instruments --cornetto, English horn, chalumeau (the early clarinet)-- which were unavailable to him for his later French production. Of course, the featured instrument is the harp, which despite its small part, is an actor in the drama. It is Orpheus's instrument, with which he accompanies himself as he tames the demons of the underworld. While the exact type of harp that Gluck would have had available for his Vienna premiere has been a matter of some speculation, the instrument would in any case not have had the pedals that create chromatic notes on harps today.

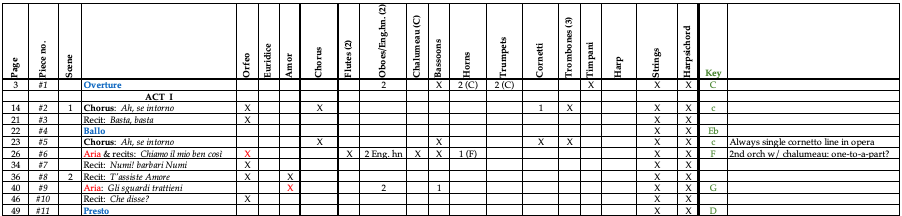

Orchestration Chart

This chart gives an overview of the work, showing which soloists and instruments are in each movement. It has also been useful in planning rehearsals, since one can see at a glance all the music that a particular musician plays. Red X's indicate major solo moments for a singer. An X in parentheses indicates that the use of that instrument is ad libitum.

This is a preview of the beginning of the chart. You can download or view a PDF of the whole chart here.

© Boston Baroque 2020

Boston Baroque Performances

Orfeo ed Euridice

March 4 & 5, 2012

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

David Gately, stage director

Gianni Di Marco, choreographer

Soloists:

Owen Willetts, Orfeo

Mary Wilson, Euridice

Courtney Huffman, Amor

May 11, 1995

Sanders Theater, Cambridge, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor

Soloists:

Jeffrey Gall, Orfeo

Marvis Martin, Euridice

Jayne West, Amor

Orfeo ed Euridice - Orchestral Suite

May 11 & 13 2000

NEC’s Jordan Hall, Boston, MA

Martin Pearlman, conductor